- 50 histoires de mondialisations : de Neandertal à Wikipédia Vincent Capdepuy Alma éditeurVincent Capdepuy

- Sylvain Rouer Débuter Le Trading Des Cryptomonnaies: Investir Dans Le Bitcoin Et La Blockchain Facilement Pour Les DébutantsBinding : Taschenbuch, Label : Independently published, Publisher : Independently published, medium : Taschenbuch, numberOfPages : 106, publicationDate : 2022-03-20, authors : Sylvain Rouer

- Les Seigneurs De L'Argent: Des Médicis Au Bitcoin (Histoire)Brand : TALLANDIER, Binding : Taschenbuch, Label : TALLANDIER, Publisher : TALLANDIER, medium : Taschenbuch, numberOfPages : 288, publicationDate : 2020-02-13

Bitcoin est une crypto-monnaie, un actif numérique conçu pour agir comme un moyen de commutation qui utilise la cryptographie pour contrôler la création et la gestion, plutôt que de s’appuyer sur le gouvernement central.[1] Le pseudonyme adopté Satoshi Nakamoto a intégré de nombreuses idées existantes de la communauté cypherpunk lors de la création de bitcoin. Au cours de l’histoire du bitcoin, il a connu une croissance rapide pour devenir une devise importante à la fois en ligne et hors ligne – à partir du milieu des années 2010, certaines entreprises ont commencé à accepter le bitcoin en plus des devises traditionnelles.[2]

Préhistoire[[[[Éditer]

Avant la sortie du bitcoin, il y avait un certain nombre de technologies de paiement numérique qui ont commencé avec des protocoles de paiement électronique basés sur l’émetteur de David Chaum et Stefan Brands.[3][4][5] Adam Back a développé hashcash, un programme de preuve de travail pour la vérification du spam. Les premières propositions de rareté numérique distribuée basées sur la crypto-monnaie ont été le b-money de Wei Dai[6] et le petit or de Nick Szabo.[7][8] Hal Finney a développé une preuve de travail réutilisable (RPOW) en utilisant le hashcash comme algorithme de preuve de travail.[9]

Cependant, dans la proposition Bit Gold qui suggérait un mécanisme de contrôle de l’inflation basé sur le collecteur, Nick Szabo a examiné certains aspects supplémentaires, y compris un protocole d’accord byzantin tolérant aux pannes basé sur des adresses de décision pour stocker et transmettre les solutions de correction chaînées, cependant, était vulnérable aux attaques Sybil.[8]

Créer[[[[Éditer]

Le 18 août 2008, le nom de domaine bitcoin.org a été enregistré.[10] Plus tard dans l’année, le 31 octobre, un lien vers un article de Satoshi Nakamoto intitulé Bitcoin: un système de paiement électronique peer-to-peer[11] a été publié dans une liste de diffusion cryptographique.[12] Ce document détaille les méthodes d’utilisation d’un réseau peer-to-peer pour générer ce qui est décrit comme « un système de transactions électroniques sans compter sur la confiance ».[13][14][15] Le 3 janvier 2009, le réseau bitcoin a rejoint Satoshi Nakamoto en tant que briseur bloc de genèse de bitcoin (bloc numéro 0), qui avait une récompense de 50 bitcoins.[13][16] Intégré dans la base de pièces de ce bloc était le texte:

The Times 03 / Jan / 2009 La chancelière au bord des autres renflouements bancaires.[17]

Le texte fait référence à un titre Les temps publié le 3 janvier 2009.[18] Cette remarque a été interprétée à la fois comme un horodatage à partir du moment de l’émergence et comme un commentaire dédaigneux sur l’instabilité causée par la banque de réserves fractionnaires.[19]:18

Le premier client bitcoin open source a été publié le 9 janvier 2009, hébergé par SourceForge.[20][21]

L’un des premiers partisans, adoptants, contributeurs au bitcoin et destinataires de la première transaction bitcoin était le programmeur Hal Finney. Finney a téléchargé le logiciel bitcoin le jour de sa sortie et a reçu 10 bitcoins de Nakamoto lors de la première transaction bitcoin au monde le 12 janvier 2009.[22][23] Les autres premiers adeptes étaient Wei Dai, créateur des prédécesseurs de Bitcoin B-Moneyet Nick Szabo, créateur des prédécesseurs du bitcoin un peu d’or.[13]

Au cours des premiers jours, Nakamoto aurait cassé 1 million de bitcoins.[24] Avant qu’il ne disparaisse de toute implication dans le bitcoin, Nakamoto a en quelque sorte remis les rênes au développeur Gavin Andresen, qui est ensuite devenu le développeur de bitcoin à la Fondation Bitcoin, la communauté bitcoin « anarchique » la plus proche d’un visage public officiel.[25]

La valeur des premières transactions bitcoin a été négociée par des particuliers lors du forum bitcoin avec une transaction remarquable de 10 000 BTC, qui a indirectement acheté deux pizzas livrées par Papa John’s.[13]

Le 6 août 2010, une vulnérabilité majeure a été détectée dans le protocole bitcoin. Les transactions n’ont pas été correctement vérifiées avant d’être incluses dans le journal des transactions ou chaîne de blocs, ce qui permet aux utilisateurs de contourner les contraintes financières du bitcoin et de créer un nombre indéfini de bitcoins.[26][27] Le 15 août, la vulnérabilité a été exploitée; plus de 184 milliards de bitcoins ont été générés en une seule transaction et envoyés à deux adresses sur le réseau. En quelques heures, la transaction a été détectée et supprimée du journal des transactions après la correction du bogue et le réseau est passé à une version mise à jour du protocole bitcoin.[28] Ce fut la seule faille de sécurité majeure trouvée et exploitée dans l’histoire du bitcoin.[26][27]

Satoshi Nakamoto[[[[Éditer]

« Satoshi Nakamoto » est censé être un pseudonyme pour la personne ou les personnes qui ont conçu le protocole bitcoin original en 2008 et lancé le réseau en 2009. Nakamoto était responsable de la création de la majorité du logiciel bitcoin officiel et était actif dans les modifications et la publication d’informations techniques. sur le forum bitcoin.[13] Il y a eu beaucoup de spéculations sur l’identité de Satoshi Nakamoto avec des suspects dont Dai, Szabo et Finney – et les démentis qui l’accompagnent.[29][30] La possibilité que Satoshi Nakamoto soit un collectif informatique dans le secteur financier européen a également été discutée.[31]

Des enquêtes sur la véritable identité de Satoshi Nakamoto ont été tentées Le new yorker et Entreprise rapide. Le New Yorkais L’enquête comprenait au moins deux candidats possibles: Michael Clear et Vili Lehdonvirta. Affaires rapides « L’enquête a révélé des circonstances liant une demande de brevet de chiffrement déposée par Neal King, Vladimir Oksman et Charles Bry le 15 août 2008, et le nom de domaine bitcoin.org qui a été enregistré 72 heures plus tard. La demande de brevet (# 20100042841) contenait des technologies de réseau et de cryptage similaires au bitcoin, et l’analyse de texte a révélé que l’expression « … impossible à inverser en termes de calcul » figurait à la fois dans la demande de brevet et dans le livre blanc du bitcoin.[11] Les trois inventeurs ont explicitement nié Satoshi Nakamoto.[32][33]

En mai 2013, Ted Nelson a émis l’hypothèse que le mathématicien japonais Shinichi Mochizuki était Satoshi Nakamoto.[34] Plus tard en 2013, les scientifiques israéliens Dorit Ron et Adi Shamir ont désigné Ross William Ulbricht, lié à la route de la soie, comme la personne possible derrière la protection. Les deux chercheurs ont fondé leur suspicion sur une analyse du réseau de transactions bitcoin.[35] Ces accusations ont été remises en question[36] et Ron et Shamir ont retiré leur demande plus tard.[37]

L’implication de Nakamoto avec le bitcoin ne semble pas s’étendre jusqu’à la mi-2010.[13] En avril 2011, Nakamoto a communiqué avec un donneur de bitcoins et a déclaré qu’il était « passé à autre chose ».[17]

Stefan Thomas, un codeur suisse et membre actif de la communauté, a dessiné les horodatages de chacun des 500 messages du forum Bitcoin de Nakamoto; Le graphique résultant a montré une forte baisse à presque aucun poste entre 5 h et 11 h, heure de Greenwich. Étant donné que ce modèle s’appliquait également les samedis et dimanches, il a suggéré que Nakamoto dormait à cette heure, et les heures de 17h00 à GMT sont de minuit à 00h00. 18 h 00, heure normale de l’Est (heure normale de l’Est de l’Amérique du Nord). D’autres indices suggéraient que Nakamoto était britannique: un titre de journal qu’il avait codé dans le bloc Genesis provenait du journal britannique Les temps, et ses messages sur le forum et ses commentaires dans le code source de bitcoin utilisaient des orthographes en anglais britannique, telles que « optimiser » et « couleur ».[13]

Une recherche sur Internet par un blogueur anonyme de textes écrits similaires au livre blanc de Bitcoin suggère que les articles « Bit d’or » de Nick Szabo ont un auteur similaire.[29] Nick a nié être Satoshi et a exprimé son opinion officielle sur Satoshi et le bitcoin dans un article en mai 2011.[38]

Dans un article de mars 2014, je Newsweek, La journaliste Leah McGrath Goodman a doublé Dorian S. Nakamoto de Temple City, en Californie, disant que Satoshi Nakamoto est le nom de naissance de l’homme. Ses méthodes et sa conclusion ont suscité de nombreuses critiques.[39][40]

En juin 2016, la London Review of Books a publié un article d’Andrew O’Hagan sur Nakamoto.[41] La véritable identité de Satoshi Nakamoto est toujours controversée.

2011[[[[Éditer]

Sur la base de l’open source de bitcoin, d’autres crypto-monnaies ont commencé à émerger.[42]

L’Electronic Frontier Foundation, un groupe à but non lucratif, a commencé à accepter les bitcoins en janvier 2011,[43] a ensuite cessé de les accepter en juin 2011, invoquant des inquiétudes quant à l’absence de précédent juridique sur les nouveaux systèmes monétaires.[44] La décision du FEP a été annulée le 17 mai 2013 lorsqu’ils ont recommencé à accepter le bitcoin.[45]

En juin 2011, WikiLeaks[46] et d’autres organisations ont commencé à recevoir des bitcoins pour les dons.

2012[[[[Éditer]

En janvier 2012, le bitcoin a été présenté comme le sujet principal d’un procès fictif sur le drame juridique de CBS La bonne épouse dans la troisième saison « Bitcoin for Dummies ». Hôte CNBC Des sommes folles, Jim Cramer, s’est joué dans une scène juridique où il témoigne qu’il ne croit pas que le bitcoin est une vraie monnaie et dit « Il n’y a pas de banque centrale pour le réglementer; il est numérique et fonctionne complètement peer to peer ».[47]

En septembre 2012, la Fondation Bitcoin a été lancée pour « accélérer la croissance mondiale du bitcoin grâce à la normalisation, la protection et la promotion du protocole open source ». Les fondateurs étaient Gavin Andresen, Jon Matonis, Patrick Murck, Charlie Shrem et Peter Vessenes.[48]

En octobre 2012, BitPay a signalé que plus de 1 000 marchands acceptaient le bitcoin selon leur service de paiement.[49] En novembre 2012, WordPress avait commencé à accepter les bitcoins.[50]

2013[[[[Éditer]

En février 2013, le processeur de paiement basé sur Bitcoin Coinbase a annoncé qu’il vendait 1 million de bitcoins en un mois pour plus de 22 $ par bitcoin.[51] L’Internet Archive a annoncé qu’il était prêt à accepter des dons tels que des bitcoins et qu’il avait l’intention de donner aux employés la possibilité de recevoir une partie de leurs salaires en monnaie bitcoin.[52]

En mars, appelé le journal des transactions bitcoin chaîne de blocs a été temporairement divisé en deux chaînes indépendantes avec des règles différentes sur la façon dont les transactions ont été acceptées. Pendant six heures, deux réseaux bitcoin ont fonctionné simultanément, chacun avec sa propre version de l’historique des transactions. Les développeurs principaux ont exigé un arrêt temporaire des transactions, ce qui a entraîné de fortes ventes.[53] Le fonctionnement normal a été restauré lorsque la majorité du réseau a été rétrogradé à la version 0.7 du logiciel bitcoin.[53] Mt. La bourse Gox a arrêté les dépôts de bitcoins courts et le taux de change a chuté de 23% à 37 $ lorsque l’événement s’est produit[54][55] avant de revenir à un niveau précédent d’environ 48 $ dans les heures suivantes.[56] Aux États-Unis, le Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) a établi des directives réglementaires pour les « monnaies virtuelles décentralisées » telles que le bitcoin, classant les mineurs de bitcoins américains vendant leurs bitcoins générés comme des entreprises de services monétaires (ou MSB), qui peuvent être soumis à l’enregistrement et à d’autres obligations légales.[57][59]

En avril, les processeurs de paiement BitInstant et Mt. gox a connu des retards de traitement en raison d’un manque de capacité[60] entraînant une baisse du taux de change du bitcoin de 266 $ à 76 $ avant de revenir à 160 $ dans les six heures.[61] Le Bitcoin a acquis une plus grande reconnaissance lorsque des services tels que OkCupid et Foodler ont commencé à l’accepter pour le paiement.[62]

Le 15 mai 2013, les autorités américaines ont saisi des comptes concernant le mont. Gox après avoir découvert qu’il n’avait pas été enregistré comme émetteur d’argent auprès de FinCEN aux États-Unis.[63][64]

Le 17 mai 2013, il a été signalé que BitInstant a traité environ 30% de l’argent vers et depuis le bitcoin, et en avril n’a facilité que 30 000 transactions,[65]

Le 23 juin 2013, il a été signalé que la Drug Enforcement Administration des États-Unis inscrivait 11,02 bitcoins parmi les actifs saisis dans un avis de tentative du procureur des États-Unis en vertu de 21 U.S.C. § 881.[66] C’était la première fois qu’une autorité prétendait avoir saisi du bitcoin.[67][68]

En juillet 2013, un projet au Kenya qui a lié le bitcoin à M-Pesa, un système de paiement mobile populaire, a été lancé dans le cadre d’une expérience visant à stimuler les paiements innovants en Afrique.[69] Au cours du même mois, le Département des changes et de la Thaïlande de la Thaïlande a déclaré que le bitcoin n’avait aucun cadre juridique et serait donc illégal, interdisant effectivement le commerce sur les échanges de bitcoins dans le pays.[70][71] Selon Vitalik Buterin, écrivain pour Bitcoin Magazine, « le sort du bitcoin en Thaïlande pourrait donner plus de crédibilité à la monnaie électronique dans certains milieux », mais il craignait que cela n’ait pas profité au bitcoin en Chine.[72]

Le 6 août 2013, le juge fédéral Amos Mazzant du district oriental du Texas du cinquième circuit a statué que les bitcoins sont « une monnaie ou une forme d’argent » (en particulier des titres tels que définis dans les lois fédérales sur les valeurs mobilières) et, en tant que tels, sont soumis à la juridiction des tribunaux,[73][74] et le ministère allemand des Finances a subventionné les bitcoins sous le terme «unité de compte» – un instrument financier – mais pas sous forme de monnaie électronique ou de monnaie fonctionnelle, une classification qui a toujours des conséquences juridiques et fiscales.[75]

En octobre 2013, le FBI a saisi environ 26 000 BTC sur le site Web de Silk Road lors de l’arrestation du propriétaire présumé Ross William Ulbricht.[76][77][78] Deux sociétés, Robocoin et Bitcoiniacs, ont lancé le premier distributeur de bitcoins au monde le 29 octobre 2013 à Vancouver, en Colombie-Britannique, au Canada, permettant aux clients de vendre ou d’acheter des devises bitcoins dans un centre de café.[79][80][81] Le géant chinois de l’internet Baidu avait autorisé les clients des services de sécurité du site à payer avec des bitcoins.[82]

En novembre 2013, l’Université de Nicosie a annoncé qu’elle accepterait le bitcoin comme paiement des frais de scolarité, le directeur financier de l’université l’appelant « l’or de demain ».[83] En novembre 2013, l’échange de bitcoins chinois BTC Chine a dépassé le Mt. basé au Japon. Gox et Bitstamp, basé en Europe, deviendront la plus grande bourse de trading de bitcoins par volume de transactions.[84]

En décembre 2013, Overstock.com[85] a annoncé son intention d’accepter le bitcoin au second semestre 2014.

Le 5 décembre 2013, la Banque populaire de Chine a interdit aux institutions financières chinoises d’utiliser des bitcoins.[86] Après l’annonce, la valeur des bitcoins a chuté,[87] et Baidu n’acceptait plus les bitcoins pour certains services.[88] L’achat de biens immobiliers avec n’importe quelle monnaie virtuelle était illégal en Chine depuis au moins 2009.[89]

2014[[[[Éditer]

En janvier 2014, Zynga[90] a annoncé qu’il testait le bitcoin pour acheter des actifs dans le jeu dans sept de ses jeux. Le même mois, le Las Vegas Casino Hotel et le Golden Gate Hotel & Casino immobilier dans le centre de Las Vegas ont annoncé qu’ils commenceraient également à accepter le bitcoin, selon un article de USA aujourd’hui. L’article indiquait également que la monnaie serait acceptée dans cinq endroits, dont la réception et certains restaurants.[91] La vitesse du réseau a dépassé 10 petahash / sec.[92] TigerDirect[93] et Overstock.com[94] a commencé à accepter le bitcoin.

Début février 2014, l’une des plus grandes bourses de Bitcoin, Mt. gox,[95] points de vente fermés en référence à des problèmes techniques.[96] À la fin du mois, le mont. Gox avait déposé une demande de mise en faillite au Japon alors que 744 000 bitcoins avaient été volés.[97] Des mois avant le dépôt, la popularité du mont. Gox avait décliné lorsque les utilisateurs avaient du mal à retirer des fonds.[98]

En juin 2014, le réseau a dépassé 100 pétahash / sec.[[[[citation requise] Le 18 juin 2014, il a été annoncé que le fournisseur de services de paiement pour bitcoin BitPay deviendrait le nouveau sponsor de St. Petersburg Bowl en vertu d’un accord de deux ans, qui a changé son nom pour Bitcoin St. Petersburg Bowl. Le bitcoin serait accepté pour les ventes de billets et de concessions au jeu dans le cadre du parrainage, et le parrainage était également payé pour utiliser le bitcoin.[99]

En juillet 2014, Newegg et Dell[100] a commencé à accepter le bitcoin.

En septembre 2014, TeraExchange, LLC, a reçu l’approbation de la Commodity Futures Trading Commission des États-Unis «CFTC» pour commencer la cotation d’un produit d’échange exagéré basé sur le prix du bitcoin. L’approbation du produit CFTC marque la première fois qu’un régulateur américain approuve un produit financier bitcoin.[101]

En décembre 2014, Microsoft a commencé à accepter le bitcoin pour acheter des jeux Xbox et des logiciels Windows.[102]

En 2014, plusieurs chansons plus légères ont célébré le bitcoin comme Ode à Satoshi[103] est sorti.[104]

Un documentaire, La montée et la montée du Bitcoin, publié en 2014, avec des interviews d’utilisateurs de bitcoins, tels qu’un programmeur informatique et un trafiquant de drogue.[105]

2015[[[[Éditer]

En janvier 2015, Coinbase a levé 75 millions de dollars dans le cadre d’un cycle de financement de la série C, battant le record précédent pour une société de bitcoins. Moins d’un an après l’effondrement du mont. L’échange Bitstamp basé à Gox, au Royaume-Uni, a annoncé que leur échange serait mis hors ligne tout en enquêtant sur un piratage qui a entraîné le vol d’environ 19000 bitcoins (équivalant à environ 5 millions de dollars américains à l’époque) à leur portefeuille chaud.[106] L’échange est resté hors ligne pendant plusieurs jours au milieu des spéculations selon lesquelles les clients avaient perdu leur argent. Bitstamp a repris ses activités le 9 janvier après avoir augmenté les mesures de sécurité et assuré aux clients que le solde de leur compte ne serait pas affecté.[107]

En février 2015, le nombre de marchands ayant accepté le bitcoin dépassait 100 000.[108]

En octobre 2015, une proposition a été soumise au consortium Unicode pour ajouter un point de code pour le symbole bitcoin.[109]

2016[[[[Éditer]

En janvier 2016, la vitesse du réseau dépassait 1 exahash / sec.[[[[citation requise]

En mars 2016, le gouvernement japonais a reconnu les monnaies virtuelles comme le bitcoin comme une fonction similaire à l’argent réel.[110] Bidorbuy, le plus grand marché en ligne sud-africain, a lancé des paiements en bitcoins pour les acheteurs et les vendeurs.[111]

En juillet 2016, des chercheurs ont publié un document montrant qu’en novembre 2013, le trading de bitcoins n’était plus motivé par des activités de «péché» mais plutôt par des sociétés légitimes.[112]

En août 2016, un important échange de bitcoins, Bitfinex, a été piraté et près de 120 000 BTC (environ 60 millions de dollars) ont été volés.[113]

En septembre 2016, le nombre de GAB Bitcoin avait doublé au cours des 18 derniers mois, atteignant 771 GAB dans le monde.[114]

En novembre 2016, l’opérateur ferroviaire suisse CFF (CFF) a mis à niveau toutes ses machines de billetterie automatisées afin que le bitcoin puisse être acheté par eux à l’aide du scanner de la machine à billetterie pour scanner l’adresse bitcoin dans une application téléphonique.[115]

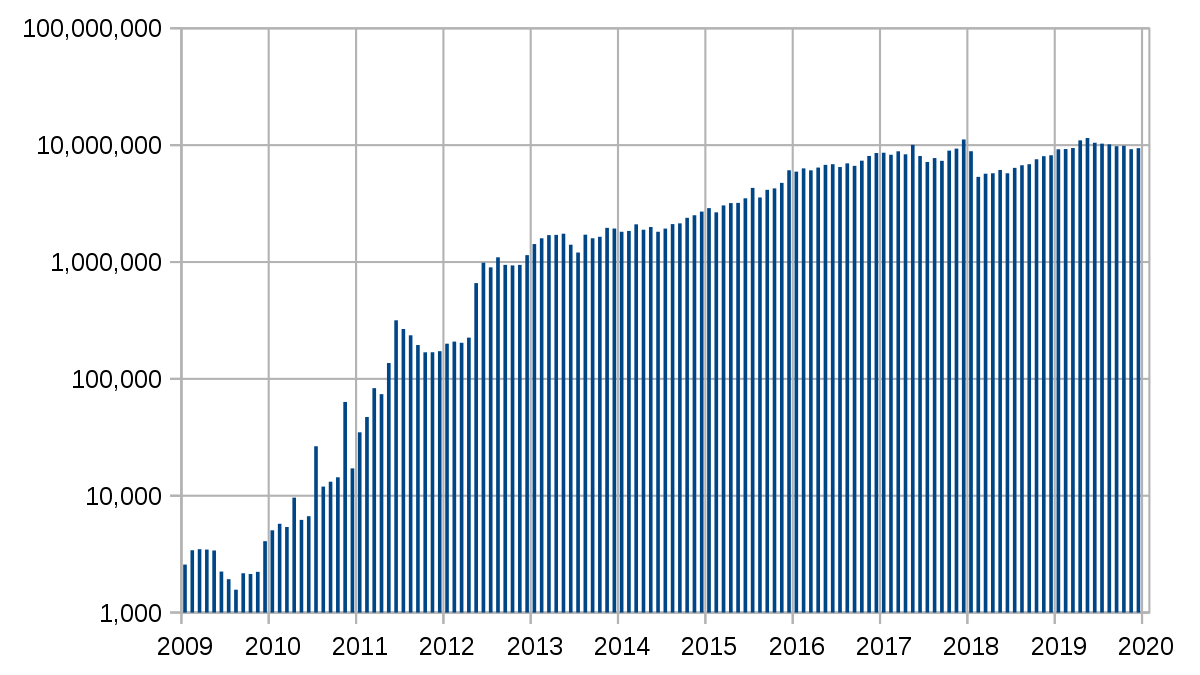

Le Bitcoin génère plus d’intérêt universitaire année après année; le nombre d’articles publiés sur Google Scholar mentionnant le bitcoin est passé de 83 en 2009 à 424 en 2012 et 3 580 en 2016. De plus, le grand livre académique (revue) a publié son premier numéro. Il est édité par Peter Rizun.

2017[[[[Éditer]

Le nombre d’entreprises acceptant le bitcoin a continué d’augmenter. En janvier 2017, NHK a signalé que le nombre de magasins en ligne acceptant le bitcoin au Japon avait augmenté de 4,6 fois au cours de l’année écoulée.[116] Le PDG de BitPay, Stephen Pair, a expliqué que le taux de transaction de l’entreprise avait augmenté de 3 × de janvier 2016 à février 2017 et a expliqué que le bitcoin se développait au sein de la chaîne d’approvisionnement B2B.[117]

Le bitcoin gagne en légitimité auprès des législateurs et des sociétés financières plus anciennes. Par exemple, le Japon a adopté une loi pour accepter le bitcoin comme moyen de paiement légal,[118] et la Russie a annoncé qu’elle légaliserait l’utilisation de crypto-monnaies telles que le bitcoin.[119]

Le trading de devises continue d’augmenter. Pour la période de six mois se terminant en mars 2017, la bourse mexicaine a vu le volume des échanges de Bitso de 1500%.[120]

Entre janvier et mai 2017, Poloniex a augmenté de plus de 600% des traders actifs en ligne et a régulièrement traité 640% de transactions en plus.[121]

En juin 2017, le symbole bitcoin dans la version Unicode 10.0 a été codé à la position U + 20BF (₿) dans le bloc des symboles monétaires.[122]

Jusqu’en juillet 2017, les utilisateurs de bitcoin conservaient un ensemble commun de règles de crypto-monnaie.[123] Le 1er août 2017, le bitcoin s’est scindé en deux monnaies numériques dérivées, la chaîne bitcoin (BTC) avec une limite de taille de bloc de 1 Mo et la chaîne Bitcoin Cash (BCH) avec une limite de taille de bloc de 8 Mo. La scission a été appelée Fourche dure Bitcoin Cash.[124]

Le 6 décembre 2017, le marché des logiciels Steam a annoncé qu’il n’accepterait plus le bitcoin comme paiement pour ses produits, citant des taux de transaction lents, une volatilité des prix et des frais de transaction élevés.[125]

2018[[[[Éditer]

Le 22 janvier 2018, la Corée du Sud a introduit un règlement exigeant que tous les commerçants de bitcoins révèlent leur identité et interdisent ainsi le commerce anonyme de bitcoins.[126]

Le 24 janvier 2018, la société de paiement en ligne Stripe a annoncé qu’elle mettrait fin à son soutien aux paiements en bitcoins d’ici la fin avril 2018, en invoquant une baisse de la demande, une augmentation des frais et des délais de transaction plus longs.[127]

2019[[[[Éditer]

En septembre 2019, il y avait 5457 guichets automatiques Bitcoin dans le monde. En août de la même année, les pays comptant le plus grand nombre de distributeurs automatiques de billets Bitcoin étaient les États-Unis, le Canada, le Royaume-Uni, l’Autriche et l’Espagne.[128]

Prix et historique des valeurs[[[[Éditer]

La crise de la dette souveraine européenne – en particulier la crise financière chypriote 2012-2013 – des déclarations du FinCEN qui ont amélioré la situation juridique de la monnaie et accru l’intérêt des médias et d’Internet ont notamment contribué à cette hausse.[129][130][131][132]

Jusqu’en 2013, presque tous les marchés avec des bitcoins étaient en dollars américains ($ US).[133][134][135]

Alors que la valorisation boursière du stock total de bitcoins approchait d’un milliard de dollars, certains commentateurs ont qualifié les prix du bitcoin de bulle.[136][137][138] Début avril 2013, le prix du bitcoin est passé de 266 $ à environ 50 $, puis est passé à environ 100 $. Pendant deux semaines à partir de la fin de juin 2013, le prix a baissé régulièrement à 70 $. Le prix a commencé à remonter et a de nouveau culminé le 1er octobre à 140 $. Le 2 octobre, la route de la soie a été défaite par le FBI. Cette saisie a provoqué un crash de foudre à 110 $. Le prix s’est rapidement rétabli et est revenu à 200 $ plusieurs semaines plus tard.[139] La dernière course est passée de 200 $ le 3 novembre à 900 $ le 18 novembre.[140] Le Bitcoin a dépassé 1000 $ le 28 novembre 2013 sur le mont. Gox.

| Date | USD: 1 BTC | Remarques |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 2009 – Mar 2010 | essentiellement rien | Pas d’échanges ou de marché, les utilisateurs étaient principalement des fans de cryptographie qui envoyaient des bitcoins à des fins de loisir qui représentaient une valeur faible ou nulle. En mars 2010, l’utilisateur « SmokeTooMuch » a vendu 10 000 BTC pour 50 $ (cumulatif), mais aucun acheteur n’a été trouvé.[141] |

| Mars 2010 | 0,003 $ | Le 17 mars 2010, BitcoinMarket.com, aujourd’hui disparu, a commencé à agir comme le premier échange de bitcoins. |

| Mai 2010 | moins de 0,01 $ | Le 22 mai 2010,[142] Laszlo Hanyecz a fait la première vraie affaire en achetant deux pizzas à Jacksonville, en Floride, pour 10 000 $; un montant qui serait de près de 750 000 $ s’il était détenu en mars 2013.[143] |

| Juillet 2010 | 0,008 $ à 0,08 $ | Le prix a augmenté de 900% en cinq jours. |

| Octobre 2010 | 0,125 $ | Le prix dépasse un peu. |

| Février 2011 – avril 2011 | 1,00 $ | Le bitcoin est associé à des dollars américains.[144] |

| 8 juin 2011 | 31,00 $ | Le sommet de la première « bulle », suivi d’une baisse des prix. |

| Déc 2011 | 2,00 $ | Le plus petit atteint en décembre après la bulle de juin. |

| Décembre 2012 | 13,00 $ | Montée lente. |

| 11 avril 2013 | 266 $ | Pour couronner une remontée des prix où une croissance de 5 à 10% était quotidienne. |

| Mai 2013 | 130 $ | Le prix est globalement stable avec une lente remontée. |

| Juin 2013 | 100 $ | Le prix est descendu lentement à 70 $ en juin avant de remonter à 110 $ en juillet. |

| Nov. 2013 | 350 $ 1242 $ | Le prix est passé de 150 $ en octobre à 200 $ en novembre, pour atteindre 1242 $ le 29 novembre 2013.[145] |

| Décembre 2013 | 600 $ – 1000 $ | Le prix s’est effondré à 600 $, s’est rétabli à 1000 $, a de nouveau chuté à 500 $. Stabilisé à 650 $ – 800 $. |

| Jan 2014 | 750 $ 1000 $ | Le prix a atteint 1 000 $ il y a peu de temps et s’est établi entre 800 $ et 900 $ pour le reste du mois. |

| Février 2014 | 550 $ 750 $ | Le prix s’est écrasé après la fermeture du mont. Gox avant de récupérer entre 600 $ et 700 $. |

| Mars 2014 | 450 $ 700 $ | Priset fortsatte att sjunka på grund av en falsk rapport om bitcoinförbud i Kina och osäkerhet om den kinesiska regeringen skulle försöka förbjuda banker att arbeta med digital valutautbyte. |

| Apr 2014 | $ 340- $ 530 | The lowest price since the 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis had been reached at 3:25 AM on 11 April[146] |

| May 2014 | $440–$630 | The downtrend first slows down and then reverses, increasing over 30% in the last days of May. |

| Mar 2015 | $200–$300 | Price fell through to early 2015. |

| Early Nov 2015 | $395–$504 | Large spike in value from $225–$250 at the start of October to the 2015 record high of $504. |

| May–June 2016 | $450–$750 | Large spike in value starting from $450 and reaching a maximum of $750. |

| July–September 2016 | $600–$630 | Price stabilized in the low $600 range. |

| October–November 2016 | $600–$780 | As the Chinese Renminbi depreciated against the US dollar, bitcoin rose to the upper $700s. |

| January 2017 | $800–$1,150 | |

| 5-12 January 2017 | $750–$920 | Price fell 30% in a week, reaching a multi-month low of $750. |

| 2-3 March 2017 | $1,290+ | Price broke above the November 2013 high of $1,242[147] and then traded above $1,290.[148] |

| 20 May 2017 | $2,000 | Price reached a new high, reaching $1,402.03 on 1 May 2017, and over $1,800 on 11 May 2017.[149] On 20 May 2017, the price passed $2,000 for the first time. |

| May–June 2017 | $2,000–$3,200+ | Price reached an all-time high of $3,000 on 12 June and is oscillating around $2,500 since then. As of 6 August 2017, the price is $3,270. |

| 14 August 2017 | $4,400 | Price passed $3,000 for the first time on 5 August 2017, then $4,000 on 12 August 2017 and $4,400 two days later. |

| 1 September 2017 | $5,013.91 | Price broke $5,000 for the first time.[150] |

| 12 September 2017 | $2,900 | Price dipped in response to China’s bitcoin ICO and exchange crackdown. |

| 13 October 2017 | $5,600 | Price shot back up in the aftermath of China’s crackdown. |

| 21 October 2017 | $6,180 | Price hit another all-time high as the impending forks drew closer. |

| 17-20 November 2017 | $7,600-8,100 | Briefly topped at $8004.59. This surge in bitcoin may be related to the 2017 Zimbabwean coup d’état. In one bitcoin exchange, 1 BTC topped at nearly $13,500, just shy of 2 times the value of the International market.[151][152] |

| 15 December 2017 | $17,900 | Price reached $17,900.[153] |

| 17 December 2017 | $19,783.06 | Price rose 5% in 24 hours, with its value being up 1,824% since 1 January 2017, to reach a new all-time high.[154] |

| 22 December 2017 | $13,800 | Price lost one third of its value in 24 hours, dropping below $14,000.[155] |

| 5 February 2018 | $6,200 | Price dropped by 50% in 16 days, falling below $7,000.[156] |

| 31 October 2018 | $6,300 | On the 10th anniversary of bitcoin, the price held steady above $6,000 during a period of historically low volatility.[157][158] |

| 7 December 2018 | $3,300 | Price briefly dipped below $3,300, a 76% drop from the previous year and a 15-month low.[159] |

A fork referring to a blockchain is defined variously as a blockchain split into two paths forward, or as a change of protocol rules. Accidental forks on the bitcoin network regularly occur as part of the mining process. They happen when two miners find a block at a similar point in time. As a result, the network briefly forks. This fork is subsequently resolved by the software which automatically chooses the longest chain, thereby orphaning the extra blocks added to the shorter chain (that were dropped by the longer chain).

March 2013[[[[Éditer]

On 12 March 2013, a bitcoin miner running version 0.8.0 of the bitcoin software created a large block that was considered invalid in version 0.7 (due to an undiscovered inconsistency between the two versions).

This created a split or « fork » in the blockchain since computers with the recent version of the software accepted the invalid block and continued to build on the diverging chain, whereas older versions of the software rejected it and continued extending the blockchain without the offending block.

This split resulted in two separate transaction logs being formed without clear consensus, which allowed for the same funds to be spent differently on each chain. In response, the Mt. Gox exchange temporarily halted bitcoin deposits.[160] The exchange rate fell 23% to $37 on the Mt. Gox exchange but rose most of the way back to its prior level of $48.[54][55]

Miners resolved the split by downgrading to version 0.7, putting them back on track with the canonical blockchain.

User funds largely remained unaffected and were available when network consensus was restored.[161] The network reached consensus and continued to operate as normal a few hours after the split.[162]

August 2017[[[[Éditer]

Two significant forks took place in August. One, bitcoin cash, was a hard fork off the main chain in opposition to the other, which was a soft fork to implement Segregated Witness.

Regulatory issues[[[[Éditer]

On 18 March 2013, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (or FinCEN), a bureau of the United States Department of the Treasury, issued a report regarding centralized and decentralized « virtual currencies » and their legal status within « money services business » (MSB) and Bank Secrecy Act regulations.[59][64] It classified digital currencies and other digital payment systems such as bitcoin as « virtual currencies » because they are not legal tender under any sovereign jurisdiction. FinCEN cleared American users of bitcoin of legal obligations[64] by saying, « A user of virtual currency is not an MSB under FinCEN’s regulations and therefore is not subject to MSB registration, reporting, and recordkeeping regulations. » However, it held that American entities who generate « virtual currency » such as bitcoins are money transmitters or MSBs if they sell their generated currency for national currency: « …a person that creates units of convertible virtual currency and sells those units to another person for real currency or its equivalent is engaged in transmission to another location and is a money transmitter. » This specifically extends to « miners » of the bitcoin currency who may have to register as MSBs and abide by the legal requirements of being a money transmitter if they sell their generated bitcoins for national currency and are within the United States.[57] Since FinCEN issued this guidance, dozens of virtual currency exchangers and administrators have registered with FinCEN, and FinCEN is receiving an increasing number of suspicious activity reports (SARs) from these entities.[163]

Additionally, FinCEN claimed regulation over American entities that manage bitcoins in a payment processor setting or as an exchanger: « In addition, a person is an exchanger and a money transmitter if the person accepts such de-centralized convertible virtual currency from one person and transmits it to another person as part of the acceptance and transfer of currency, funds, or other value that substitutes for currency. »[59]

In summary, FinCEN’s decision would require bitcoin exchanges where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies to disclose large transactions and suspicious activity, comply with money laundering regulations, and collect information about their customers as traditional financial institutions are required to do.[64][164][165]

Jennifer Shasky Calvery, the director of FinCEN said, « Virtual currencies are subject to the same rules as other currencies. … Basic money-services business rules apply here. »[64]

In its October 2012 study, Virtual currency schemes, the European Central Bank concluded that the growth of virtual currencies will continue, and, given the currencies’ inherent price instability, lack of close regulation, and risk of illegal uses by anonymous users, the Bank warned that periodic examination of developments would be necessary to reassess risks.[166]

In 2013, the U.S. Treasury extended its anti-money laundering regulations to processors of bitcoin transactions.[167][168]

In June 2013, Bitcoin Foundation board member Jon Matonis wrote in Forbes that he received a warning letter from the California Department of Financial Institutions accusing the foundation of unlicensed money transmission. Matonis denied that the foundation is engaged in money transmission and said he viewed the case as « an opportunity to educate state regulators. »[169]

In late July 2013, the industry group Committee for the Establishment of the Digital Asset Transfer Authority began to form to set best practices and standards, to work with regulators and policymakers to adapt existing currency requirements to digital currency technology and business models and develop risk management standards.[170]

In 2014, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filed an administrative action against Erik T. Voorhees, for violating Securities Act Section 5 for publicly offering unregistered interests in two bitcoin websites in exchange for bitcoins.[171]

By December 2017, bitcoin futures contracts began to be offered, and the US Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) was formally settling the futures daily.[172][173]

By 2019, multiple trading companies were offering services around bitcoin futures.[174]

Theft and exchange shutdowns[[[[Éditer]

Bitcoins can be stored in a bitcoin cryptocurrency wallet. Theft of bitcoin has been documented on numerous occasions. At other times, bitcoin exchanges have shut down, taking their clients’ bitcoins with them. UNE Wired study published April 2013 showed that 45 percent of bitcoin exchanges end up closing.[175]

On 19 June 2011, a security breach of the Mt. Gox bitcoin exchange caused the nominal price of a bitcoin to fraudulently drop to one cent on the Mt. Gox exchange, after a hacker used credentials from a Mt. Gox auditor’s compromised computer illegally to transfer a large number of bitcoins to himself. They used the exchange’s software to sell them all nominally, creating a massive « ask » order at any price. Within minutes, the price reverted to its correct user-traded value.[176][177][178][179][180][181] Accounts with the equivalent of more than US$8,750,000 were affected.[178]

In July 2011, the operator of Bitomat, the third-largest bitcoin exchange, announced that he had lost access to his wallet.dat file with about 17,000 bitcoins (roughly equivalent to US$220,000 at that time). He announced that he would sell the service for the missing amount, aiming to use funds from the sale to refund his customers.[182]

In August 2011, MyBitcoin, a now defunct bitcoin transaction processor, declared that it was hacked, which caused it to be shut down, paying 49% on customer deposits, leaving more than 78,000 bitcoins (equivalent to roughly US$800,000 at that time) unaccounted for.[183][184]

In early August 2012, a lawsuit was filed in San Francisco court against Bitcoinica – a bitcoin trading venue – claiming about US$460,000 from the company. Bitcoinica was hacked twice in 2012, which led to allegations that the venue neglected the safety of customers’ money and cheated them out of withdrawal requests.[185][186]

In late August 2012, an operation titled Bitcoin Savings and Trust was shut down by the owner, leaving around US$5.6 million in bitcoin-based debts; this led to allegations that the operation was a Ponzi scheme.[187][188][189][190] In September 2012, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission had reportedly started an investigation on the case.[191]

In September 2012, Bitfloor, a bitcoin exchange, also reported being hacked, with 24,000 bitcoins (worth about US$250,000) stolen. As a result, Bitfloor suspended operations.[192][193] The same month, Bitfloor resumed operations; its founder said that he reported the theft to FBI, and that he plans to repay the victims, though the time frame for repayment is unclear.[194]

On 3 April 2013, Instawallet, a web-based wallet provider, was hacked,[195] resulting in the theft of over 35,000 bitcoins[196] which were valued at US$129.90 per bitcoin at the time, or nearly $4.6 million in total. As a result, Instawallet suspended operations.[195]

On 11 August 2013, the Bitcoin Foundation announced that a bug in a pseudorandom number generator within the Android operating system had been exploited to steal from wallets generated by Android apps; fixes were provided 13 August 2013.[197]

In October 2013, Inputs.io, an Australian-based bitcoin wallet provider was hacked with a loss of 4100 bitcoins, worth over A$1 million at time of theft. The service was run by the operator TradeFortress. Coinchat, the associated bitcoin chat room, was taken over by a new admin.[198]

On 26 October 2013, a Hong Kong–based bitcoin trading platform owned by Global Bond Limited (GBL) vanished with 30 million yuan (US$5 million) from 500 investors.[199]

Mt. Gox, the Japan-based exchange that in 2013 handled 70% of all worldwide bitcoin traffic, declared bankruptcy in February 2014, with bitcoins worth about $390 million missing, for unclear reasons. The CEO was eventually arrested and charged with embezzlement.[200]

On 3 March 2014, Flexcoin announced it was closing its doors because of a hack attack that took place the day before.[201][202][203] In a statement that once occupied their homepage, they announced on 3 March 2014 that « As Flexcoin does not have the resources, assets, or otherwise to come back from this loss [the hack], we are closing our doors immediately. »[204] Users can no longer log into the site.

Chinese cryptocurrency exchange Bter lost $2.1 million in BTC in February 2015.

The Slovenian exchange Bitstamp lost bitcoin worth $5.1 million to a hack in January 2015.

The US-based exchange Cryptsy declared bankruptcy in January 2016, ostensibly because of a 2014 hacking incident; the court-appointed receiver later alleged that Cryptsy’s CEO had stolen $3.3 million.

In August 2016, hackers stole some $72 million in customer bitcoin from the Hong Kong–based exchange Bitfinex.[205]

In December 2017, hackers stole 4,700 bitcoins from NiceHash a platform that allowed users to sell hashing power.[206] The value of the stolen bitcoins totaled about $80M.[207]

On 19 December 2017, Yapian, a company that owns the Youbit cryptocurrency exchange in South Korea, filed for bankruptcy following a hack, the second in eight months.[208]

Taxation and regulation[[[[Éditer]

In 2012, the Cryptocurrency Legal Advocacy Group (CLAG) stressed the importance for taxpayers to determine whether taxes are due on a bitcoin-related transaction based on whether one has experienced a « realization event »: when a taxpayer has provided a service in exchange for bitcoins, a realization event has probably occurred and any gain or loss would likely be calculated using fair market values for the service provided. »[209]

In August 2013, the German Finance Ministry characterized bitcoin as a unit of account,[75][210] usable in multilateral clearing circles and subject to capital gains tax if held less than one year.[210]

On 5 December 2013, the People’s Bank of China announced in a press release regarding bitcoin regulation that whilst individuals in China are permitted to freely trade and exchange bitcoins as a commodity, it is prohibited for Chinese financial banks to operate using bitcoins or for bitcoins to be used as legal tender currency, and that entities dealing with bitcoins must track and report suspicious activity to prevent money laundering.[211] The value of bitcoin dropped on various exchanges between 11 and 20 percent following the regulation announcement, before rebounding upward again.[212]

Arbitrary blockchain content[[[[Éditer]

Bitcoin’s blockchain can be loaded with arbitrary data. In 2018 researchers from RWTH Aachen University and Goethe University identified 1,600 files added to the blockchain, 59 of which included links to unlawful images of child exploitation, politically sensitive content, or privacy violations. « Our analysis shows that certain content, e.g. illegal pornography, can render the mere possession of a blockchain illegal. »[213]

Interpol also sent out an alert in 2015 saying that « the design of the blockchain means there is the possibility of malware being injected and permanently hosted with no methods currently available to wipe this data ».[214]

références[[[[Éditer]

- + Jerry Brito; Andrea Castillo (2013). « Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers » (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Récupéré 22 October 2013.

- + A History of Bitcoin. Monetary Economics: International Financial Flows, Financial Crises, Regulation & Supervision eJournal. Social Science Research Network (SSRN). Accessed 8 January 2018.

- + Chaum, David (1983). « Blind signatures for untraceable payments » (PDF). Advances in Cryptology Proceedings of Crypto. 82 (3): 199–203. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0602-4_18. ISSN 978-1-4757-0604-8.

- + Chaum, David; Fiat, Amos; Naor, Moni. « Untraceable Electronic Cash » (PDF). Lecture Notes in Computer Science.

- + Chaum, David; Brands, Stefan (4 January 1999). « « Minting’ electronic cash ». IEEE Spectrum special issue on electronic money, February 1997. IEEE. Récupéré 17 September 2018.

- + Dai, W (1998). « b-money ». Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Récupéré 5 December 2013.

- + Szabo, Nick. « Bit Gold ». Unenumerated. Blogspot. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Récupéré 5 December 2013.

- + une b Tsorsch, Florian; Scheuermann, Bjorn (15 May 2015). « Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey of Decentralized Digital Currencies » (PDF). Récupéré 24 June 2015.

- + « Reusable Proofs of Work ». Archived from the original on 22 December 2007.

- + Bernard, Zoë (2 December 2017). « Everything you need to know about Bitcoin, its mysterious origins, and the many alleged identities of its creator ». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Récupéré 15 June 2018.

- + une b Nakamoto, Satoshi (31 October 2008). « Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System » (PDF). Récupéré 20 December 2012.

- + Finley, Klint (31 October 2018). « After 10 Years, Bitcoin Has Changed Everything—And Nothing ». Wired. Récupéré 9 November 2018.

- + une b c ré e F g Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). « The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin ». Wired. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Récupéré 13 October 2012.

- + « Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper ». 31 October 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + « Satoshi’s posts to Cryptography mailing list ». Mail-archive.com. Récupéré 26 March 2013.

- + « Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer ». Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + une b Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). « The Crypto-Currency ». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Récupéré 16 February 2013.

- + Elliott, Francis; Duncan, Gary (3 January 2009). « Chancellor Alistair Darling on brink of second bailout for banks ». The Times. Récupéré 27 April 2018.

- + Pagliery, Jose (2014). Bitcoin: And the Future of Money. Triumph Books. ISSN 9781629370361. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Récupéré 20 January 2018.

- + Nakamoto, Satoshi (9 January 2009). « Bitcoin v0.1 released ». Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- + « SourceForge.net: Bitcoin ». Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + Peterson, Andrea (3 January 2014). « Hal Finney received the first Bitcoin transaction. Here’s how he describes it ». The Washington Post.

- + Popper, Nathaniel (30 August 2014). « Hal Finney, Cryptographer and Bitcoin Pioneer, Dies at 58 ». NYTimes. Récupéré 2 September 2014.

- + McMillan, Robert. « Who Owns the World’s Biggest Bitcoin Wallet? The FBI ». Wired. Condé Nast. Récupéré 7 October 2016.

- + Bosker, Bianca (16 April 2013). « Gavin Andresen, Bitcoin Architect: Meet The Man Bringing You Bitcoin (And Getting Paid In It) ». The Huffington Post. Récupéré 21 October 2016.

- + une b Sawyer, Matt (26 February 2013). « The Beginners Guide To Bitcoin – Everything You Need To Know ». Monetarism. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + une b « Vulnerability Summary for CVE-2010-5139 ». National Vulnerability Database. 8 June 2012. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Récupéré 22 March 2013.

- + Nakamoto, Satoshi. « [bitcoin-list] ALERT – we are investigating a problem » (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Récupéré 15 October 2013.

- + une b « Satoshi Nakamoto is (probably) Nick Szabo ». LikeInAMirror. WordPress. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Récupéré 5 December 2013.

- + Weisenthal, Joe (19 May 2013). « Here’s The Problem With The New Theory That A Japanese Math Professor Is The Inventor Of Bitcoin ». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Récupéré 19 May 2013.

- + Bitcoin Inventor Satoshi Nakamoto is Anonymous-style Cell from Europe Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- + Penenberg, Adam. « The Bitcoin Crypto-Currency Mystery Reopened ». FastCompany. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Récupéré 16 February 2013.

- + Greenfield, Rebecca (11 October 2011). « The Race to Unmask Bitcoin’s Inventor(s) ». The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Récupéré 16 February 2013.

- + « I Think I Know Who Satoshi Is ». YouTube TheTedNelson Channel. 18 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.

- + John Markoff (23 November 2013). « Study Suggests Link Between Dread Pirate Roberts and Satoshi Nakamoto ». New York Times.

- + Trammell, Dustin D. « I Am Not Satoshi ». Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Récupéré 27 November 2013.

- + Wile, Rob. « Researchers Retract Claim Of Link Between Alleged Silk Road Mastermind And Founder Of Bitcoin ». Business Week. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Récupéré 17 December 2013.

- + « Newsweek Thinks It Found the Real « Satoshi Nakamoto » … and His Name Is Satoshi Nakamoto ». slate.com. 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014.

- + Leah McGrath Goodman (6 March 2014). « The Face Behind Bitcoin ». Newsweek. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Récupéré 6 March 2014.

- + Greenberg, Andy (6 March 2014). « Bitcoin Community Responds To Satoshi Nakamoto’s ‘Uncovering’ With Disbelief, Anger, Fascination ». Forbes.com. Forbes. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Récupéré 3 April 2014.

- + Nakamoto, Andrew O’Hagan on the many lives of Satoshi (30 June 2016). « The Satoshi Affair ». pp. 7–28. Récupéré 3 March 2017 – via London Review of Books.

- + Espinoza, Javier (22 September 2014). « Is It Time to Invest in Bitcoin? Cryptocurrencies Are Highly Volatile, but Some Say They Are Worth It ». The Wall Street Journal. Récupéré 28 June 2016.

- + Rainey Reitman (20 January 2011). « Bitcoin – a Step Toward Censorship-Resistant Digital Currency ». Electronic Frontier Foundation. Récupéré 7 December 2017.

- + EFF said they « generally don’t endorse any type of product or service. »« EFF and Bitcoin | Electronic Frontier Foundation ». Eff.org. 20 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Récupéré 7 December 2017.

- + Cindy Cohn; Peter Eckersley; Rainey Reitman & Seth Schoen (17 May 2013). « EFF Will Accept Bitcoins to Support Digital Liberty ». Electronic Frontier Foundation. Récupéré 7 December 2017.

- + Greenberg, Andy (14 June 2011). « WikiLeaks Asks For Anonymous Bitcoin Donations ». Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011. Récupéré 22 June 2011.

- + Toepfer, Susan (16 January 2012). « « The Good Wife’ Season 3, Episode 13, ‘Bitcoin for Dummies’: TV Recap ». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- + Matonis, Jon. « Bitcoin Foundation Launches To Drive Bitcoin’s Advancement ». Forbes. Récupéré 20 May 2017.

- + Browdie, Brian (11 September 2012). « BitPay Signs 1,000 Merchants to Accept Bitcoin Payments ». American Banker. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014.

- + Skelton, Andy (15 November 2012). « Pay Another Way: Bitcoin ». WordPress. Récupéré 24 April 2014.

- + Ludwig, Sean (8 February 2013). « Y Combinator-backed Coinbase now selling over $1M Bitcoin per month ». VentureBeat. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- + Mandalia, Ravi (22 February 2013). « The Internet Archive Starts Accepting Bitcoin Donations ». Parity News. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Récupéré 28 February 2013.

- + une b Lee, Timothy (11 March 2013). « Major glitch in Bitcoin network sparks sell-off; price temporarily falls 23% ». arstechnica.com. Récupéré 15 February 2015.

- + une b Lee, Timothy (12 March 2013). « Major glitch in Bitcoin network sparks sell-off; price temporarily falls 23% ». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Récupéré 14 June 2017.

- + une b Blagdon, Jeff (12 March 2013). « Technical problems cause Bitcoin to plummet from record high, Mt. Gox suspends deposits ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Récupéré 21 March 2018.

- + « Bitcoin Charts ». Archived from the original on 9 May 2014.

- + une b Lee, Timothy (20 March 2013). « US regulator Bitcoin Exchanges Must Comply With Money Laundering Laws ». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Récupéré 14 June 2017.

Bitcoin miners must also register if they trade in their earnings for dollars.

- + une b c « Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies » (PDF). Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2013. Récupéré 19 March 2013.

- + Roose, Kevin (8 April 2013) « Inside the Bitcoin Bubble: BitInstant’s CEO – Daily Intelligencer ». Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.. Nymag.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2013.

- + « Bitcoin Exchange Rate ». Bitcoinscharts.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Récupéré 15 August 2013.

- + Van Sack, Jessica (27 May 2013). « Why Bitcoin makes cents ». Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Récupéré 15 August 2013.

- + Dillet, Romain. « Feds Seize Assets From Mt. Gox’s Dwolla Account, Accuse It Of Violating Money Transfer Regulations ». Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Récupéré 15 May 2013.

- + une b c ré e Berson, Susan A. (2013). « Some basic rules for using ‘bitcoin’ as virtual money ». American Bar Association. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Récupéré 26 June 2013.

- + Taylor, Colleen. « With $1.5M Led By Winklevoss Capital, BitInstant Aims To Be The Go-To Site To Buy And Sell Bitcoins ». TechCrunch. Récupéré 20 May 2017.

- + Cohen, Brian. « Users Bitcoins Seized by DEA ». Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Récupéré 14 October 2013.

- + « The National Police completes the second phase of the operation « Ransomware« « . El Cuerpo Nacional de Policía. Récupéré 14 October 2013.

- + Sampson, Tim (2013). « U.S. government makes its first-ever Bitcoin seizure ». The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Récupéré 15 October 2013.

- + Jeremy Kirk (11 July 2013). « In Kenya, Bitcoin linked to popular mobile payment system ». Cio.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Récupéré 15 August 2013.

- + Andrew Trotman (30 July 2013). « Virtual currency Bitcoin not welcome in Thailand in possible setback to mainstream ambitions ». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Récupéré 15 August 2013.

- + Maierbrugger, Arno (30 July 2013). « Thailand first country to ban digital currency Bitcoin ». Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Récupéré 3 August 2013.

- + « Virtual currency Bitcoin not welcome in Thailand in possible setback to mainstream ambitions ». bitcoinsalvation. 4 July 2015. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Récupéré 4 July 2015.

- + Farivar, Cyrus (7 August 2013). « Federal judge: Bitcoin, « a currency, » can be regulated under American law ». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Récupéré 15 August 2013.

- + « Securities and Exchange Commission v. Shavers et al, 4:13-cv-00416 (E.D.Tex.) ». Docket Alarm, Inc. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Récupéré 14 August 2013.

- + une b Vaishampayan, Saumya (19 August 2013). « Bitcoins are private money in Germany ». Marketwatch. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + « After Silk Road seizure, FBI Bitcoin wallet identified and pranked ». Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- + « Silkroad Seized Coins ». Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + Hill, Kashmir. « The FBI’s Plan For The Millions Worth Of Bitcoins Seized From Silk Road ». Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- + « World’s first Bitcoin ATM goes live in Vancouver Tuesday ». CBC. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + « Vancouver to host world’s first Bitcoin ATM ». Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Récupéré 27 January 2019.

- + « The world’s first Bitcoin ATM is coming to Canada next week ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Récupéré 29 October 2013.

- + Kapur, Saranya (15 October 2013). « China’s Google Is Now Accepting Bitcoin ». businessinsider.com. Business Insider, Inc. Récupéré 26 December 2013.

- + « Cypriot University to Accept Bitcoin Payments ». abc News. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Récupéré 24 November 2013.

- + Natasha Lomas (18 November 2013). « As Chinese Investors Pile Into Bitcoin, China’s Oldest Exchange, BTC China, Raises $5M From Lightspeed ». TechCrunch. Récupéré 10 January 2014.

- + Dante D’Orazio (21 December 2013). « Online retailer Overstock.com plans to accept Bitcoin payments next year ». Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Récupéré 5 January 2014.

- + Kelion, Leo (18 December 2013). « Bitcoin sinks after China restricts yuan exchanges ». bbc.com. BBC. Récupéré 20 December 2013.

- + « China bans banks from bitcoin transactions ». The Sydney Morning Herald. Reuters. 6 December 2013. Récupéré 31 October 2014.

- + « Baidu Stops Accepting Bitcoins After China Ban ». Bloomberg. New York. 7 December 2013. Récupéré 11 December 2013.

- + « China bars use of virtual money for trading in real goods ». English.mofcom.gov.cn. 29 June 2009. Récupéré 10 January 2014.

- + Carl Franzen (4 January 2014). « Zynga tests Bitcoin payments for seven online games ». Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Récupéré 5 January 2014.

- + Trejos, Nancy. « Las Vegas casinos adopt new form of currency: Bitcoins ». USA Today. Récupéré 21 January 2014.

- + « We’ve just reached 10 petahash per second! ». 20 December 2013.

- + Jane McEntegart (26 January 2014). « TigerDirect is Now Accepting Bitcoin As Payment ». Tom’s hardware. Récupéré 28 August 2014.

- + Vaishampayan, Saumya (9 January 2014). « Bitcoin now accepted on Overstock.com through VC-backed Coinbase ». marketwatch.com. Wall Street Journal. Récupéré 10 February 2014.

- + « MtGox gives bankruptcy details ». bbc.com. BBC. 4 March 2014. Récupéré 13 March 2014.

- + Biggs, John (10 February 2014). « What’s Going On With Bitcoin Exchange Mt. Gox? ». TechCrunch. Récupéré 26 February 2014.

- + « MtGox bitcoin exchange files for bankruptcy ». bbc.com. BBC. 28 February 2014. Récupéré 18 April 2014.

- + Swan, Noelle (28 February 2014). « MtGox bankruptcy: Bitcoin insiders saw problems with the exchange for months ». csmonitor.com. The Christian Science Monitor. Récupéré 18 April 2014.

- + Casey, Michael J. (18 June 2014). « BitPay to Sponsor St. Petersburg Bowl in First Major Bitcoin Sports Deal ». The Wall Street Journal. Récupéré 18 June 2014.

- + Flacy, Mike (19 July 2014). « Dell, Newegg Start Accepting Bitcoin as Payment ». Digital Trends. Récupéré 5 August 2014.

- + Callaway, Claudia; Greebel, Evan; Moriarity, Kathleen; Xethalis, Gregory; Kim, Diana. « First Bitcoin Swap Proposed ». The National Law Review. Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. Récupéré 15 September 2014.

- + Warren, Tom (11 December 2014). « Microsoft now accepts Bitcoin to buy Xbox games and Windows apps ».

- + « Ode to Satoshi ». Récupéré 4 December 2017.

- + Paul Vigna (18 February 2014). « BitBeat: Mt. Gox’s Pyrrhic Victory ». Money Beat. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Récupéré 30 September 2014.

‘Ode to Satoshi’ is a bluegrass-style song with an old-timey feel that mixes references to Satoshi Nakamoto and blockchains (and, ahem, ‘the fall of old Mt. Gox’) with mandolin-picking and harmonicas.

- + Kenigsberg, Ben (2 October 2014). « Financial Wild West ». Le New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Récupéré 8 May 2015.

- + Srivastava, Shivam (6 January 2015). « Bitcoin exchange Bitstamp suspends service after security breach ». reuters.com. Reuters. Récupéré 24 January 2015.

- + Novak, Marja (9 January 2015). « Bitcoin exchange Bitstamp says to resume trading on Friday ». reuters.com. Reuters. Récupéré 24 January 2015.

- + Cuthbertson, Anthony (4 February 2015). « Bitcoin now accepted by 100,000 merchants worldwide ». International Business Times. IBTimes Co., Ltd. Récupéré 20 November 2015.

- + Shirriff, Ken (2 October 2015). « Proposal for addition of bitcoin sign » (PDF). unicode.org. Unicode. Récupéré 3 November 2015.

- + « Japan OKs recognizing virtual currencies as similar to real money ». 4 March 2016.

- + « Activating and Using Bitcoin as a Payment Option ». Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Récupéré 15 January 2020.

- + Tasca, Paolo; Liu, Shaowen; Hayes, Adam (1 July 2016), The Evolution of the Bitcoin Economy: Extracting and Analyzing the Network of Payment Relationships, p. 36, SSRN 2808762,

By November, 2013, the amount of inflows attributable to ”sin” entities had shrunk significantly to just 3% or less of total transactions.

- + Coppola, Frances (6 August 2016). « Theft And Mayhem In The Bitcoin World ». Forbes. Récupéré 15 August 2016.

- + « Number of Bitcoin ATMs Has More Than Doubled In Past 18 Months ». 1 October 2016.

- + « SBB: Make quick and easy purchases with Bitcoin ». Récupéré 3 March 2017.

- + « ビットコイン 利用可能店舗が1年で4.6倍に ». 9 January 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Récupéré 9 January 2017.

- + « The Bitcoin Fee Market ». 7 March 2017.

our transaction growth of nearly 3x […] Many of the businesses we’ve signed up over the years have started using BitPay for B2B supply chain payments.

- + Kharpal, Arjun. « Bitcoin value rises over $1 billion as Japan, Russia move to legitimize cryptocurrency ».

- + Colibasanu, Antonia. « Here’s why Russia is opening the door to cryptocurrencies ».

- + « Mexican Bitcoin Adoption is Untold Story of the Last Six Months. Nearly 1500% volume growth on its largest exchange. Over $4M USD equivalent per week now ». 27 March 2017.

- + « INDUSTRY GROWTH AND ITS EFFECT ON POLONIEX ». 16 May 2017.

- + « Unicode 10.0.0 ». Unicode Consortium. 20 June 2017. Récupéré 20 June 2017.

- + Popper, Nathaniel (25 July 2017). « Some Bitcoin Backers Are Defecting to Create a Rival Currency ». Le New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Récupéré 28 July 2017.

- + Smith, Jake (11 August 2017). « The Bitcoin Cash Hard Fork Will Show Us Which Coin Is Best ». Fortune. Récupéré 13 August 2017.

- + Liao, Shannon (6 December 2016). « Steam no longer accepting bitcoin due to ‘high fees and volatility« « . The Verge. Récupéré 8 August 2019.

- + « Bitcoin price latest: Cryptocurrency plunges as traders in South Korea forced to identify themselves ». The Independent. Récupéré 1 February 2018.

- + « Stripe to ditch Bitcoin payment support ». BBC. 24 January 2018. Récupéré 25 January 2018.

- + « Bitcoin – additional information ». 9 March 2020. Récupéré 13 March 2020.

- + Traverse, Nick (3 April 2013). « Bitcoin’s Meteoric Rise ». Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- + Bustillos, Maria (2 April 2013). « The Bitcoin Boom ». Archived from the original on 13 March 2014.

- + Seward, Zachary (28 March 2013). « Bitcoin, up 152% this month, soaring 57% this week ». Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Récupéré 9 April 2013.

- + « A Bit expensive ». The Economist. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- + (in English) Bitcoin Charts (price) Archived 28 March 2011 at WebCite

- + (in English) History of Bitcoin (Bitcoin wiki) Archived 13 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- + « History – Bitcoin ». en.bitcoin.it. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Récupéré 4 December 2013.

- + Estes, Adam (28 March 2013). « Bitcoin is now a billion dollar industry ». Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Récupéré 2 November 2013.

- + Salmon, Felix. « The Bitcoin Bubble and the Future of Currency ». Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Récupéré 9 April 2013.

- + Ro, Sam (3 April 2013). « Art Cashin: The Bitcoin Bubble ». Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.

- + « Bitcoin value drops after FBI shuts Silk Road drugs site ». BBC News. 3 October 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Récupéré 4 December 2013.

- + « Mt. Gox graph ». Bitcoinity.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Récupéré 4 December 2013.

- + Vigna, Paul; Casey, Michael J. (27 January 2015). The age of cryptocurrency : how bitcoin and digital money are challenging the global economic order. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 79. ISBN 9781250065636.

- + « Why Bitcoin Matters ». Récupéré 4 January 2016.

- + Merchant, Brian (26 March 2013). « This Pizza Cost $750,000 ». Motherboard. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Récupéré 13 January 2017.

- + Leos Literak. « Bitcoin dosáhl parity s dolarem ». Abclinuxu.cz. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Récupéré 4 December 2013.

- + « Bitcoin worth almost as much as gold ». CNN.com. 29 November 2013. Récupéré 24 February 2017.

- + BitcoinWisdom – Live Bitcoin/Litecoin charts Archived 11 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- + « Bitcoin is now worth more than an ounce of gold for the first time ever ». Marketwatch.com. 2 March 2017. Récupéré 2 March 2017.

- + « Bitcoin price exceeds gold for first time ever ». CNN.com. 3 March 2017. Récupéré 9 March 2017.

- + « Bitcoin crosses $1,800 for the first time adding $3 billion in market cap in just four days ». 11 May 2017.

- + Boivard, Charles (1 September 2017). « Bitcoin Price Tops $5,000 For First Time ». Forbes. Récupéré 9 October 2017.

- + Robert Brand, Brian Latham, and Godfrey Marawanyika (15 November 2017). « Zimbabwe Doesn’t Have Its Own Currency and Bitcoin Is Surging ». Bloomberg L.P. Récupéré 16 November 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- + Riley, Charles. « Bitcoin costs as much as $13,000 in Zimbabwe ». CNNMoney. Récupéré 16 November 2017.

- + Kelly, Jemima (15 December 2017). « Bitcoin hits new record high as warnings grow louder ». Reuters. Récupéré 15 December 2017.

- + « Bitcoin Hits a New Record High, But Stops Short of $20,000 ». Fortune. Récupéré 8 December 2018.

- + Shane, Daniel (22 December 2017). « Bitcoin lost a third of its value in 24 hours ». CNN. Récupéré 23 December 2017.

- + Cheng, Evelyn (5 February 2018). « Bitcoin continues to tumble, hitting its lowest point since November ». CNBC. Récupéré 5 February 2018.

- + Martin, Shane (31 October 2018). « Bitcoin is 10 years old today — here’s a look back at its crazy history ». BI. Récupéré 3 November 2018.

- + Lee, Justina (30 October 2018). « Bitcoin Is Now the Least Volatile Since Late 2016 ». Bloomberg. Récupéré 3 November 2018.

- + Rooney, Kate (7 December 2018). « Bitcoin price pain continues as the cryptocurrency plummets to a 15-month low ». CNBC. Récupéré 18 December 2019.

- + Karpeles, Mark. « Bitcoin blockchain issue – bitcoin deposits temporarily suspended ». Mt. Gox. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Récupéré 12 March 2013.

- + « 11/12 March 2013 Chain Fork Information ». Bitcoin Project. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Récupéré 12 March 2013.

- + « Bitcoin software bug has been rapidly resolved ». ecurrency. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- + « Remarks From Under Secretary of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David S. Cohen on ‘Addressing the Illicit Finance Risks of Virtual Currency« « . United States Department of the Treasury. 18 March 2014.

- + Lee, Timothy (19 March 2013). « New Money Laundering Guidelines Are A Positive Sign For Bitcoin ». Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Récupéré 21 March 2018.

- + Faiola, Anthony; Farnam, T.W. (4 April 2013). « The rise of the bitcoin: Virtual gold or cyber-bubble? ». Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- + « Virtual Currency Schemes » (PDF). European Central Bank. October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2013.

- + « Bitcoin, the nationless electronic cash beloved by hackers, bursts into financial mainstream ». Fox News. 11 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013.. Fox News (11 April 2013). Retrieved on 20 April 2013.

- + « Bitcoin Currency, Hackers Make Money, Investing in Bitcoins, Scams – AARP ». Archived from the original on 22 March 2014.. Blog.aarp.org (19 March 2013). Retrieved on 20 April 2013.

- + Coldewey, Devin (24 June 2013). « Bitcoin losing shine after hitting the spotlight ». NBC News. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013.

- + Tsukayama, Hayley (30 July 2013). « Bitcoin, others set up standards group ». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013.

- + Casey, Brian (23 July 2014). « Bitcoin – Is Anyone In Charge? ». The National Law Review. Récupéré 15 September 2014.

- + Bloomberg (12 December 2017). « Winklevoss Twins Say Futures Are Just the Beginning for Bitcoin ». Fortune. Récupéré 12 May 2020.

- + Urban, Rob; Russo, Camila (9 December 2017). « Bitcoin Futures Trading Brings Crypto Into Mainstream ». Bloomberg. Récupéré 12 May 2020.

- + Leising, Matthew (6 September 2019). « Bitcoin Futures on ICE Grow Nearer With Custody Warehouse Start ». Bloomberg. Récupéré 9 September 2019.

- + « Study: 45 percent of Bitcoin exchanges end up closing ». Récupéré 28 April 2013.

© Condé Nast UK 2013

Wired.co.uk (26 April 2013). - + Karpeles, Mark (30 June 2011). « Clarification of Mt Gox Compromised Accounts and Major Bitcoin Sell-Off ». Tibanne Co. Ltd. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014.

- + « Bitcoin Report Volume 8 – (FLASHCRASH) ». YouTube BitcoinChannel. 19 June 2011. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014.

- + une b Mick, Jason (19 June 2011). « Inside the Mega-Hack of Bitcoin: the Full Story ». DailyTech. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Récupéré 24 November 2013.

- + Lee, Timothy B. (19 June 2011) « Bitcoin prices plummet on hacked exchange ». Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Récupéré 14 June 2017., Ars Technica

- + Karpeles, Mark (20 June 2011) Huge Bitcoin sell off due to a compromised account – rollback, Mt.Gox Support Archived 20 June 2011 at WebCite

- + Chirgwin, Richard (19 June 2011). « Bitcoin collapses on malicious trade – Mt Gox scrambling to raise the Titanic ». The Register. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.

- + Dotson, Kyt (1 August 2011) « Third Largest Bitcoin Exchange Bitomat Lost Their Wallet, Over 17,000 Bitcoins Missing ». Archived from the original on 15 February 2014.. SiliconAngle

- + Jeffries, Adrianne (8 August 2011) « MyBitcoin Spokesman Finally Comes Forward: « What Did You Think We Did After the Hack? We Got Shitfaced« « . Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Récupéré 24 November 2013.. BetaBeat

- + Jeffries, Adrianne (19 August 2011) « Search for Owners of MyBitcoin Loses Steam ». Archived from the original on 4 April 2014.. BetaBeat

- + Geuss, Megan (12 August 2012) « Bitcoinica users sue for $460k in lost bitcoins ». Archived from the original on 11 April 2014.. Ars Technica

- + Peck, Morgen (15 August 2012) « First Bitcoin Lawsuit Filed In San Francisco ». Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.. IEEE Spectrum

- + « Bitcoin ponzi scheme – investors lose US$5 million in online hedge fund ». RT. 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- + Jeffries, Adrianne (27 August 2012). « Suspected multi-million dollar Bitcoin pyramid scheme shuts down, investors revolt ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Récupéré 21 March 2018.

- + Mick, Jason (28 August 2012). « « Pirateat40″ Makes Off $5.6M USD in BitCoins From Pyramid Scheme ». DailyTech. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Récupéré 24 November 2013.

- + Mott, Nathaniel (31 August 2012). « Bitcoin: How a Virtual Currency Became Real with a $5.6M Fraud ». PandoDaily. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Récupéré 24 November 2013.

- + Foxton, Willard (2 September 2012) « Bitcoin ‘Pirate’ scandal: SEC steps in amid allegations that the whole thing was a Ponzi scheme ». The Daily Telegraph. London. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.. The Telegraph

- + « Bitcoin theft causes Bitfloor exchange to go offline ». BBC News. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014.

- + Goddard, Louis (5 September 2012). « Bitcoin exchange BitFloor suspends operations after $250,000 theft ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014.

- + Chirgwin, Richard (25 September 2012). « Bitcoin exchange back online after hack ». PC World. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014.

- + une b Cutler, Kim-Mai (3 April 2013). « Another Bitcoin Wallet Service, Instawallet, Suffers Attack, Shuts Down Until Further Notice ». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Récupéré 12 April 2013.

- + « Transaction details for bitcoins stolen from Instawallet ». Archived from the original on 19 October 2013.. Blockchain.info (3 April 2013). Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- + Chirgwin, Richard (12 August 2013). « Android bug batters Bitcoin wallets / Old flaw, new problem ». The Register. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. ● Original Bitcoin announcement: « Android Security Vulnerability ». bitcoin.org. 11 August 2013. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013.

- + « Australian Bitcoin bank hacked ». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Récupéré 9 November 2013.. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- + « Hong Kong Bitcoin Trading Platform Vanishes with millions ». Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Récupéré 18 November 2013.

- + « Ex-boss of MtGox bitcoin exchange arrested in Japan over lost $390m ». The Guardian. 1 August 2015.

- + « Flexcoin – flexing Bitcoins to their limit ». malwareZero. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Récupéré 9 March 2014.

- + « Bitcoin bank Flexcoin shuts down after theft ». Reuters. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Récupéré 9 March 2014.

- + « Bitcoin bank Flexcoin pulls plug after cyber-robbers nick $610,000 ». The Register. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Récupéré 9 March 2014.

- + « Flexcoin homepage ». Flexcoin. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Récupéré 9 March 2014.

- + « All Bitfinex clients to share 36% loss of assets following exchange hack ». The Guardian. 7 August 2016.

- + « NiceHash ». www.facebook.com. Récupéré 7 December 2017.

- + Lee, Dave; Millions ‘stolen’ in NiceHash Bitcoin heist; BBC News; 8 December 2017; https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-42275523

- + « A South Korean cryptocurrency exchange files for bankruptcy after hack, says users will get 75% of assets for now ». CNBC. 19 December 2017.

- + Stewart, David D.; Soong Johnston, Stephanie D. (29 October 2012). « 2012 TNT 209-4 NEWS ANALYSIS: VIRTUAL CURRENCY: A NEW WORRY FOR TAX ADMINISTRATORS?. (Release Date: OCTOBER 17, 2012) (Doc 2012-21516) ». Tax Notes Today. 2012 TNT 209-4 (2012 TNT 209–4).

- + une b Nestler, Franz (16 August 2013). « Deutschland erkennt Bitcoins als privates Geld an (Germany recognizes Bitcoin as private money) ». Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Récupéré 24 November 2013.

- + 2013-12-05, 中国人民银行等五部委发布《关于防范比特币风险的通知》, People’s Bank of China Archived 22 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- + 2013-12-06, China bans banks from bitcoin transactions, The Sydney Morning Herald Archived 23 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- + Roman Matzutt; Jens Hiller; Martin Henze; Jan Henrik Ziegeldorf; Dirk Mullmann; Oliver Hohlfeld; Klaus Wehrle (2018). « A Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Arbitrary Blockchain Content on Bitcoin » (PDF). Financial Cryptography and Data Security 2018. pp. 6–8.

- + « INTERPOL cyber research identifies malware threat to virtual currencies ». Interpol. Récupéré 25 March 2020.